Visa exemptions for certain nationalities rei...

read more

After our May 2021 Circular alerting clients about the rising risk of drug trafficking in cargo vessels leaving Brazilian ports, the trend continues

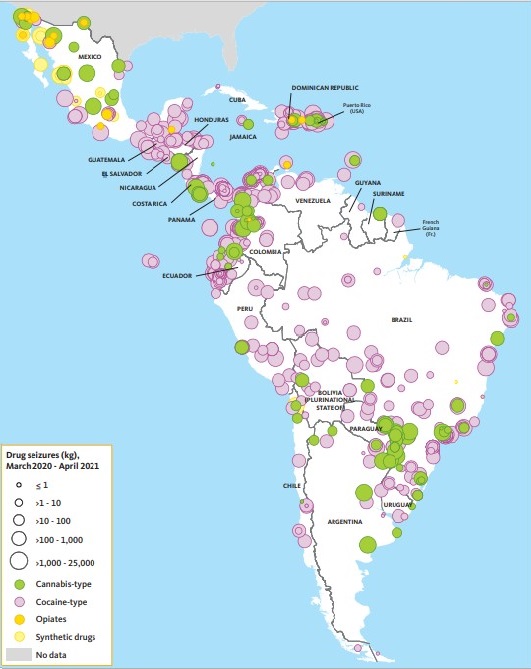

According to the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), almost 90% of all cocaine seized globally is smuggled by sea. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports that competing drug producers are increasingly striving to push up quality and productivity while lowering wholesale prices in the face of soaring demand and high profitability. Thus, maritime drug smuggling should maintain the upward trend for the near future as the methods and routes employed by the traffickers evolve and adapt to increase efficiency and dodge law enforcement agencies.

In Brazil, drug smuggling remains the most frequently committed crime within the national port system. Large quantities of cocaine intercepted from shipping containers throughout 2021 suggest that this method remains smugglers’ top logistic choice to move large amounts of the drug around. However, equally worrying, several bulk carriers were contaminated with the illicit substance last year while loading cargoes in Brazil, often with overwhelming consequences for shipowners and crews.

This update covers current trends in maritime drug trafficking in the country and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the local drug trade. It briefly explains Brazil’s drug enforcement framework and comments on the many port-security flaws in breach of the ISPS Code, as identified in an audit recently completed by Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts (TCU).

Brazil has nearly 8,000 kilometres of open coastline and shares more than 8,000 km of borders, essentially unprotected, with the three largest global cocaine producers, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru. In addition to entry points into the vastness of the Amazon region in the north of the country, landlocked Paraguay to the south is an important transhipment point for cocaine trafficked out of Bolivia and sent across the border to Brazil for domestic use and shipping abroad.

With its continental dimensions, extensive unpatrolled shores and inland waterways, Brazil plays a strategic role as a maritime hub for the trafficking of cocaine produced in the Andean countries and shipped to markets in Europe, Africa, and Asia, where demand remains strong throughout the pandemic.

UNODC ranks Brazil as the second-largest consumer market for the illegal stimulant drug after the United States, putting the country behind Colombia and the US in terms of amounts of cocaine intercepted in recent years.

Container shortages, disruptions to the global supply chain, and travel bans that restricted the ability of air couriers to move around during the pandemic have prompted organised crime groups to explore alternative ways to convey drug shipments to the avid international market. In the past year, there has been the emergence of systematic drug trafficking in bulk carriers to move large shipments of cocaine overseas, either inside the vessels or attached to their hulls and underwater structures, sea chests in particular. Even after restrictions related to COVID-19 have been eased, this trend continues in full swing thru 2022.

The discovery of drugs inside containers that were neither packed nor sealed by the ocean carrier (FCL shipments) rarely brings about legal consequences for shipowners or crews, other than eventual delays to the vessel for official investigations when the contaminated cargo unit was already on board. On the other hand, drugs concealed directly in vessels compartments, even in locations below the waterline and physically inaccessible to the crew, inevitably transfer the risk of detection – and criminal prosecution – to innocent third parties, usually the vessel’s officers.

Final figures from UNODC and the Brazilian authorities on drug seizures have not yet been released. Still, preliminary reports point to a high number of interceptions and quantities confiscated from containers and vessels in the last year. It also signals improvement in intelligence-sharing among law enforcement agencies in Brazil and abroad.

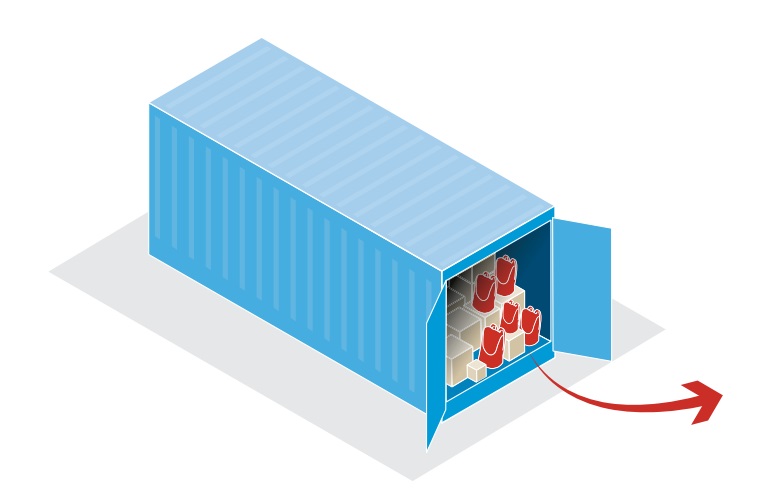

Containerised drug shipments

Despite advances in security technologies, controls, and detection tools, such as scanners, sniffer dogs, and risk management, cocaine continues to be inventively smuggled in containers through Brazilian ports routinely.

Whichever method is adopted, drugs in containers typically involve replacing the original security seal with a forged one after the product is placed inside the cargo unit. Accomplices at the other end collect the illegal shipment then put on another seal, which is sometimes left next to the drugs, before cargo delivery to the consignee. These schemes often involve the corruption of truck drivers, packers, and port workers at both ends. When drugs are incorporated into legitimate goods, corrupt shippers’ officials or cargo owners can also be implicated.

Amid growing threats of interception of containers for drug trafficking, in January 2022, leading global container operator Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) and its Brazilian subsidiary MEDLOG announced that they have decided to immediately halt their inland logistics operations across Brazil until further notice. Services included container haulage, stuffing, multimodal pre-carriage, and pre-stacking.

Shippers can rely on the Special Enclosures for Export Customs Clearance – REDEX services. These are non-bonded facilities in a secondary area, which can be inside shippers’ premises, for those who want to speed up customs clearance processes at a lower cost and better protect their shipments until delivery to the loading port terminal. However, these facilities are not out of the reach of organised crime groups.

Drugs on bulk carriers

There are precedents of drug trafficking in cargo compartments and hulls of cargo liners, typically containerships and ro-ro vessels. However, the first incidents involving tramp bulk carriers in Brazilian ports surfaced in 2021, when dozens of these vessels were unwittingly employed in the drug trade.

While some bulk carriers were fortunate enough to detect smuggling attempts at the loading port, others did not notice the contamination – or were not thoroughly decontaminated after local police intervention – until they arrived at ports of discharge in Southeast Asia and West Africa. The vessels were detained and crews arrested after local drug enforcement and customs agencies detected or became aware of the drugs. Although the bulkers were released months later, some crewmembers remained in custody, facing prosecution in a foreign jurisdiction away from their homes and families.

Regardless of the current trend of targeting bulk carriers, which are numerous in the national ports due to the high volume of agriproducts exported by the country in recent years, all cargo vessels are at risk of being passively contaminated with illicit drugs. Ultimately, it all comes down to the opportunities presented to drug traffickers and how unattended the vessel is, whether moored alongside the berth or anchored off the port.

Cocaine caches recovered from sea chests of bulk carriers. Source: Brazilian Customs/Hellenic Coast Guard

In January 2022, Federal Police arrested a professional Spanish diver from the Canary Islands as he was about to dive off a boat to cache drugs onto the hull of a bulk carrier berthed at Santos. The Spaniard was wanted by the police of Espirito Santo accused of hiding packages of cocaine into the sea chest of a vessel off Vitoria last December. In 2021, divers associated with different organised crime groups were arrested in Federal Police operations in Paranagua, Vitoria, and Rio de Janeiro. Dozens of arrest orders have been issued against individuals accused of taking part in shipborne drug smuggling.

COVID-19 fallout on seaborne trafficking

UNODC data reflect the maritime community’s general perception of a significant increase in seaborne drug trafficking in the last few years. The UN agency reports that global drug markets rebounded quickly after the COVID-19 outbreak, as drug traffickers devised new smuggling methods and improved existing ones.

During the ongoing pandemic, the dynamics of drug trafficking accelerated. Among other adverse effects, it resulted in the growing use of cargo vessels to transport ever-increasing shipments of illicit drugs. UNODC also reports that contactless methods for delivering drugs to end-users have also been enhanced during lockdown measures and curfews in consumer markets, further boosting demand for the narcotic.

Despite travel restrictions and eventual lockdowns imposed by states and municipalities throughout the pandemic in Brazil, cargo handling in the national port system was not disturbed. In fact, the country has broken records in port handling volumes and agricultural products’ exports in the last couple of years.

Drug seizures from containers (and, lately, from bulk carriers and other cargo vessels) remain at elevated levels, indicating no significant disruptions in Brazilian ports’ drug supply chain. On the contrary, the ongoing international public health emergency has hastened the development of new smuggling techniques.

Port of Santos

Santos is the largest port in Latin America in size and variety of cargo profiles. The majority of containerised goods and agricultural products exported by the country are flown through the port complex on the coast of São Paulo, which records the highest numbers of drug incidents and amounts of cocaine intercepted.

Last year, following a new trend, the bustling port in Southeast Brazil recorded at least a dozen cases involving bulk carriers loaded with agriproducts where smugglers attempted – and in some cases succeeded – to dispatch substantial volumes of cocaine to foreign ports. Waterproof drug packages were discovered in cargo compartments buried in legitimately loaded bulk cargoes. The drug was also recovered in expressive quantities from sea chests at the bottom of the vessels, accessible only to divers.

To illustrate the end of another eventful year of drug busts in the port complex of Santos, in the last week of December 2021, a joint action involving the Federal Police and Customs seized large amounts of pure cocaine in port terminals. In one case, 504 kilograms of the drug were hidden in big bags with sugar for Tema in Ghana; in another case, 730 kg were concealed in concentrated orange juice inside a container bound for Valencia, Spain. The next day, the task force managed to recover other 715 kilograms of cocaine from sugar bags destined for the South African port of Durban.

Oddly enough, there seem to be so many containers filled with cocaine travelling through the world’s ports that some find their way back. In the first week of January 2022, at the first drug seizure of the year in Santos, the Federal Police found 59 kilograms of cocaine hidden in the insulation of an empty reefer container that had just arrived from Philadelphia.

In the last week of January 2022, the Federal Police teamed up with the Customs and Military Police. They recovered three packages with about 230 kilograms of cocaine from the sea chest of a vessel bound for Belgium. No one was arrested.

Elsewhere in Brazil

Other Brazilian ports that have also reported incidents where substantial amounts of drugs were seized from containers or bulk carriers include, but are certainly not limited to, Paranaguá, Vitória, Itaguaí (Rio de Janeiro), Natal, and Santarém, among others.

Although larger ports offer a broader range of opportunities for drug trafficking, all national ports and cargo vessels are potential targets for criminal organisations, regardless of the ISPS Code security level prevailing during the vessel’s call.

A large number of drug busts in recent weeks denotes an increase in the supply of cocaine to the market. It also indicates the effectiveness of the efforts devised by law enforcement agencies, considering that they are invariably poorly funded and lack primary resources to try to keep up with the advance of organised drug trafficking in Brazilian ports and waterways.

Maritime police and drug enforcement (Federal Police)

Unlike other continental coastal countries, Brazil has no coast guard. The Federal Constitution establishes that, in addition to immigration controls, the duties of the Federal Police include maritime, airport and border police. The Federal Police are the federal authority to combat drugs and international trafficking without prejudice to the actions of other governmental agencies.

Although the Federal Police oversee drug policies at the federal level, drug enforcement activities in Brazil are decentralised, as are data on drug seizures in ports and vessels in Brazilian waters. Each of the 27 states and the Federal District administers and finances its police forces and legislates on drug policies within its jurisdiction.

There is a severe imbalance in the budget and financial resources among the federation states. For example, the wealthy state of São Paulo is better equipped and funded to fight crime than the underdeveloped Amazonas and Pará in North Brazil. The two Amazon states are the largest federative units in territorial extension, accounting for a third of the entire Brazilian territory.

The Federal Police and Customs authorities have been cooperating more regularly with each other and with state-level public security forces to crack down on drug trafficking in a more concerted and planned manner. Nevertheless, given the disparity of principles and practices adopted among federal and state authorities, an integrated approach to tackling international drug trafficking will hardly work effectively without a thorough overhaul of the current legal framework and more financial resources to invest in equipment and police intelligence.

Public security in ports (Conportos)

The National Commission for Public Security in Ports, Terminals, and Waterways (Conportos) is responsible for managing public security systems and policies in Brazilian ports, port facilities, and territorial waters and ensuring compliance with relevant legislation, including that of the ISPS Code. Conportos comprises representatives from different federal agencies and ministries, including the Customs and the National Waterway Transport Agency (ANTAQ). Under the purview of the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, the collegiate body is also responsible for monitoring criminal offences and security breaches within its domains and reporting them to the relevant federal agency in accordance with the regulations.

Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) scrutinised the performance of the Federal Police and Conportos for not fulfilling their functional duties and responsibilities in combating seaborne drug trafficking and promoting public security in Brazilian ports and waterways. In November 2020, the court launched an audit process to review the two federal bodies in light of the relevant legislation.

The audit evaluated the organisation and operation of maritime police activities in the port complexes of Santos, Paranaguá, Rio Grande, Suape (near Recife), Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Itajaí and Vitória. These ports were chosen for moving the most significant annual volumes of export containers, according to ANTAQ.

TCU’s summary conclusion, published in June 2021, was that, due to lack of basic infrastructure, the Maritime Police Special Centres (NEPOM) of the Federal Police at Brazilian ports only partially fulfil their functions of maritime police. NEPOMs lack workforce and vehicles to patrol port areas minimally. Their small fleet of boats (many of them confiscated from criminals and not designed for maritime patrol) is over ten years old, is inadequate and poorly maintained.

The Court also considered that port facilities do not fully comply with the port public security regulation. TCU verified flaws in the compliance with minimum statutory security standards, such as the absence of risk assessment or port facility security plans, lack of designation of security supervisor and the inexistence of prevention of access by unauthorised persons. Conportos up-to-date security data with the Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS), managed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The Commission also does not collect information on inspections conducted by the State Public Safety Commissions in Ports, Terminals, and Waterways (Cesportos).

As a result of the audit, TCU ordered the Federal Police to develop an action plan with measures to be adopted to restructure the operation of the NEPOMs. The federal court ordered Conportos to establish a scheduled timeline for the adequacy of all ports and port facilities under its supervision to comply with the legislation regulating the ISPS Code security requirements in Brazil. TCU gave the Federal Police and Conportos six months to present the required action plans and schedules. So far, none of these authorities has commented on or responded to the audit’s findings.

Our Circular covering Drug Smuggling on Bulk Carriers out of Brazil of May 2021 provides detailed information on the shipborne drug problem and examples of where drugs are hidden inside containers and vessels. The publication also offers practical advice on preventive and responsive measures to help combat drug trafficking in vessels calling at Brazilian ports.

Please read our disclaimer.

Related topics:

Rua Barão de Cotegipe, 443 - Sala 610 - 96200-290 - Rio Grande/RS - Brazil

Telephone +55 53 3233 1500

proinde.riogrande@proinde.com.br

Rua Itororó, 3 - 3rd floor

11010-071 - Santos, SP - Brazil

Telephone +55 13 4009 9550

proinde@proinde.com.br

Av. Rio Branco, 45 - sala 2402

20090-003 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Brazil

Telephone +55 21 2253 6145

proinde.rio@proinde.com.br

Rua Professor Elpidio Pimentel, 320 sala 401 - 29065-060 – Vitoria, ES – Brazil

Telephone: +55 27 3337 1178

proinde.vitoria@proinde.com.br

Rua Miguel Calmon, 19 - sala 702 - 40015-010 – Salvador, BA – Brazil

Telephone: +55 71 3242 3384

proinde.salvador@proinde.com.br

Av. Visconde de Jequitinhonha, 209 - sala 402 - 51021-190 - Recife, PE - Brazil

Telephone +55 81 3328 6414

proinde.recife@proinde.com.br

Rua Osvaldo Cruz, 01, Sala 1408

60125-150 – Fortaleza-CE – Brazil

Telephone +55 85 3099 4068

proinde.fortaleza@proinde.com.br

Tv. Joaquim Furtado, Quadra 314, Lote 01, Sala 206 - 68447-000 – Barcarena, PA – Brazil

Telephone +55 91 99393 4252

proinde.belem@proinde.com.br

Av. Dr. Theomario Pinto da Costa, 811 - sala 204 - 69050-055 - Manaus, AM - Brazil

Telephone +55 92 3307-0653

proinde.manaus@proinde.com.br

Rua dos Azulões, Sala 111 - Edifício Office Tower - 65075-060 - São Luis, MA - Brazil

Telephone +55 98 99101-2939

proinde.belem@proinde.com.br