Visa exemptions for certain nationalities rei...

read more

While piracy and shipboard armed robberies have fallen on par with global trends, attacks on barges and ships in the Amazon waterways have escalated in intensity and actual violence, particularly incidents involving fuel shipments

Spanning nine states in Brazil’s North, Northeast and Central-West regions, the Amazon rainforest occupies nearly 60% of the national territory. Despite its vast geographical area, less than 13% of the population lives there, contributing only a tiny fraction to the national GDP and economic activity.

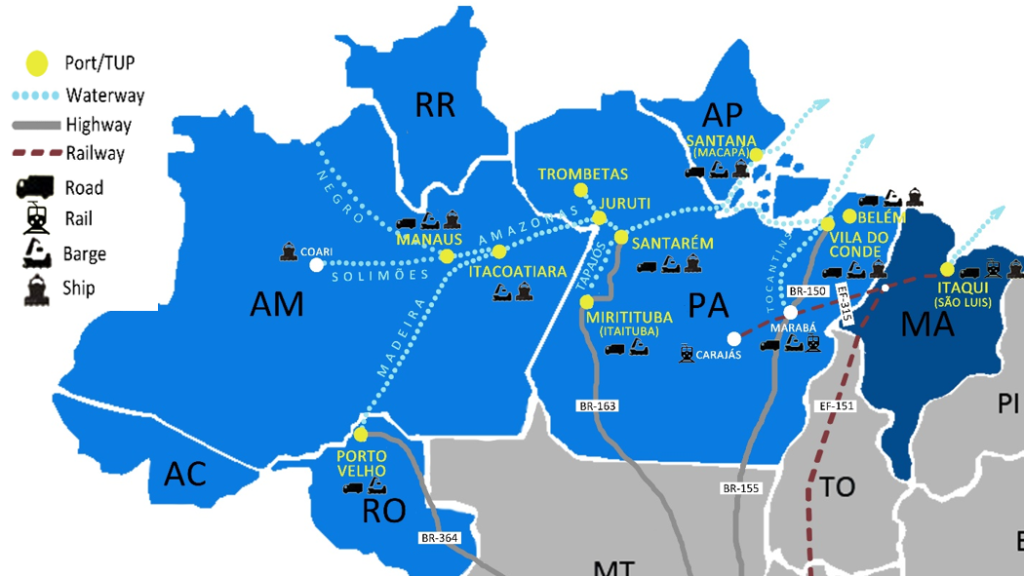

In the absence of paved roads connecting the region, the main routes for shifting raw materials and finished products are the rivers across the states of Amazonas and Rondônia to the west of the Amazon and Pará and Amapá to the east, the latter state with no overland connection to the rest of the country.

The Brazilian Amazon is home to some of the so-called Northern Arc ports, including Manaus, Itacoatiara, Santarém, Trombetas, Juruti, Vila do Conde (Barcarena), Belém, and Santana (Macapá).

Although the region features the lowest national demographic density and socioeconomic, its pace of economic growth in recent years has been higher than the average of other states, driven by investments in logistics infrastructure and expansion of barge stations and riverport facilities to outflow commodities mined in the northern states, such as iron, bauxite and manganese ores, and ever-growing shares of exports of Brazil’s record-breaking agricultural production, standing out as a competitive and greener alternative to the bottlenecks of traditional ports in the South and Southeast regions.

Barge convoys propelled by pushers or tugboats, ferries and small tankers are present throughout the Amazon, where goods are handled between dozens of so-called “TUP” (Private Use Terminal, Portuguese), “ETC” (Cargo Transhipment Station) and “IP4” (Small-Sized Port Facility) scattered along the inland waterways.

The incremented cargo shipping activities in the Northern Arc, prompted by the booming agribusiness, led to an increasing demand for barging services to move goods and supplies between ETCs, TUPs and public ports.

The largest concentrations of cargo barges and small river ships are seen on the rivers Madeira (Porto Velho and Humaitá), Negro-Solimões-Amazon (Coari, Manaus, Itacoatiara and Macapá), and Tapajós (Miritituba and Santarém) Barging operations are also frequent between Manaus and Vila do Conde (Barcarena) and Belém through the Breves Straits.

According to data from the maritime authority, over the last decade, around a thousand accidents and navigation facts on the Brazilian coast and inland waterways were investigated per year. These incidents involved an average of 238 deaths each year, an alarming 26% fatality rate.

Most fatalities occurred on passenger ferries and small craft, such as canoes, motorboats, and dinghies. Unsurprisingly, given the wide regional prevalence of rivercraft over other modes of transport, the highest proportion of accidents involving bodily injury and loss of life was recorded on the Amazon, particularly in waterways in the states of Amazonas and Pará. Tragically, many of these accidents involved scalping (due to hair trapping in improvised outboard motors), especially in small-sized skiffs, locally known as “rabetas” and “voadeiras”.

After personal injury incidents, other recurring cases in the region in recent years have been related to explosion or fire, sinking, collision and allision of all types of ships, from rudimentary canoes, pleasure craft and passenger boats to barge convoys and small-sized cargo vessels.

Considering the challenges posed by the huge geographical area, seasonality of some strategic waterways and a growing number of ships calling at the Northern Arc ports, serious navigation accidents involving ocean vessels, such as hard groundings, collisions, and spills, are relatively rare in the Amazon waterways.

However, due to the vastness of the region and the dearth of local salvage and response resources and expertise, when they do happen, incidents involving oceangoing vessels tend to be much more time-consuming – and expensive – to deal with than if they had happened elsewhere in the country.

Alongside fishing and subsistence farming, illegal river mining has been an alternative source of income for the poorer riverside population for decades, mainly upstream of the Madeira River and other tributaries near Porto Velho in Rondônia, where dredging rafts can be seen panning for gold undisturbed.

Unlit clandestine rafts and dredgers engaged in gold mining are a constant danger to commercial navigation, predominantly in the dry season when activity is intensified, and rows of rafts clog the rivers becoming a significant navigation threat to barge convoys and small ships.

Mosquito-borne diseases are endemic throughout the Amazon rainforest, where almost all domestic cases of malaria are recorded. Diseases transmitted by the Aedes mosquitoes, such as dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika virus, are prevalent in the region.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Brazilian Ministry of Health recommend yellow fever vaccination for all visitors to the Amazon, who should take precautions to avoid mosquito bites, including implementing and maintaining an effective integrated vector management plan in compliance with the WHO International Health Regulations (IHR 2005).

Brazil does not have a coast guard as such. In its role of maritime authority, the Brazilian Navy is the national authority responsible for implementing and enforcing regulations on waterway traffic along the coast and rivers to safeguard ship security and protect human life and the environment.

The Federal Police, in turn, conduct maritime and border police functions in the repression and investigation of international crimes, such as illegal immigration and smuggling of weapons, drugs and wildlife. At the same time, the state secretariats of public security, through the civil (judiciary) police and the military (ostensive) police, are responsible for applying criminal law and repressing crimes committed in the inland waterways under their jurisdiction, including theft and armed robbery.

These institutions operate in a fragmented, disconcerted manner, and each force has its own organisational arrangement with little information sharing among themselves and no standard policy to tackle waterborne trafficking and other drug-related offences.

Federal and state public security forces chronically lack manpower and minimum equipment to curb unlawful activities along the thousands of miles of inland waterways and borders.

There are no specific measures in place in the Amazonian states of Amazonas, Rondônia and Amapá to inhibit and repress crimes in the rivers.

Years ago, the government of Pará created the Grupamento Fluvial de Segurança Pública – GFlu (River Police Group) to patrol the waterfront of the capital Belém and areas with high crime rates. GFlu has an outpost on the Breves Straits, which links the Amazon River to the Pará River towards Vila do Conde (Barcarena), Belém and the Atlantic Ocean. Breves Straits is a strategic passage for convoys and cabotage ships that transport goods from the Manaus Free Trade Zone and other ports upstream for distribution to the rest of the country and has a high incidence of armed robberies.

But again, as active as they are, police forces are generally understaffed and rely on a small fleet of boats and other supporting vehicles and equipment for patrols and tactical actions over a vast geographical area. Given limited resources, including fuel shortage, police forces tend to operate closer to densely populated cities and public ports, leaving isolated stretches of waterway unpoliced.

Petty pilferages aboard riverine passenger ships and convoys carrying cargo through the Amazon have always existed. There are no reliable estimates on the incidence of armed robbery in the region due to the fragmented organisational arrangements of public security forces. Nevertheless, industry sources and local media reports indicate an evident increase in the number of cases, stolen volumes, and actual violence by the criminals, known locally as “river rats”, against crews and passengers.

The river rats are ruthless. They ambush passenger boats and cargo barges, mainly after dark, on remote, secluded stretches of rivers where telecommunications do not reach. Crews and passengers are at the mercy of the criminals, who are locals and know the riverways well enough to easily flee after an attack.

Because they are increasingly well-armed and equipped, perpetrators also dare to board convoys underway in broad daylight, outnumbering crewmembers and security guards and quickly gaining control. In some cases, they even wear military outfits to confuse crews.

The Brazilian energy matrix is highly renewable, with more than 80% of its composition comprising hydroelectric, solar, wind and other clean sources, with no less than four of the five leading national hydroelectric plants based in the Amazon Basin. However, while the region generates about a quarter of the national electricity output, its residents consume just over 10% of the energy generated.

Although the Amazon is a significant supplier of hydropower to the rest of the country, many of its inhabitants do not have access to this energy source due to a precarious distribution network system. Most Amazonian states are not connected to the national power grid, so their energy demand is primarily supplied by numerous local thermoelectric plants that burn fossil fuels, mainly diesel oil. An estimated one million people in the region live without permanent access to electricity, having only a few hours a day of power supplied by diesel oil or gasoline generators when available.

In addition to mineral and agricultural products, another commodity frequently transported up and down the river is fuel, mainly diesel oil and gasoline, which moves the boats, the primary means of transport in the region, and feeds the generators of riverside communities that live farther away from the cities out of reach of power plants.

The supply of fuels, especially hard-to-get diesel oil, is vital for the subsistence of the riverside population of the Amazon, whether to power thermoelectric plants or portable generators. Despite its regional necessity, most diesel oil consumed in the region is shipped from other parts of the country or abroad.

Diesel oil is also a strategic product that literally fuels criminal activities in the Amazon. Due to their high value, it is no wonder that fuel consignments are the most attractive targets for river rats.

As attacks increased in number and intensity, carriers and cargo interests stepped up security measures, including employing armed escorts on convoys of high-value cargo such as electronics, foodstuffs, and fuel. In response, river marauders, often linked to and financed by large criminal factions, have equipped themselves with heavy weaponry, communication equipment, and barges to transfer stolen goods to land, further escalating the armed conflict.

Many attacks against river fuel convoys have resulted in gunfire between criminals and security providers. There are reports of injuries and deaths on both sides, including law enforcement officers. Given the highly flammable payloads, fires and explosions resulting from shootouts are potential threats to the lives of people on board and the environment.

Besides cargo, bunkers and stores, river robbers frequently steal personal belongings and physically assault or traumatise crew, passengers, and security guards, many of whom are left tied up and blindfolded for hours – sometimes days – until the perpetrators finish and escape unhurriedly. Damage to navigation and communication equipment to delay distress calls is also frequent.

So confident in impunity, these criminals do not mind that it may take hours for fuel loads (and eventually the bunkers on board) to be unloaded onto clandestine tank barges, sometimes involving rudimentary pumping methods.

The National Federal of Waterway Navigation Companies (Fenavega) and the Union of Waterway Navigation Companies in the State of Amazonas (Sindarma) estimate annual losses worth over USD 21 million in goods stolen in the Amazon rivers. Even though barges and tankers transporting fuel loads are generally assisted by escort boats or security guards on board, 70% of attacks are directed at them.

All Amazonian waterways are potentially at risk of cargo theft, particularly fuels. The incidence of river raids is higher near oil terminals or refineries, the Manaus Free Trade Zone and stretches between Porto Velho and Manaus and Manaus and Parintins, as well as the Breves Straits.

The situation worsens at this time of the year with the onset of the dry season in the Amazon. As shallower rivers reduce speed, and navigation route options, besides preventing night navigation, convoys transporting fuel and other high-value-added products are even more vulnerable to the action of criminals.

The Federal Police and state police forces regulate and oversee privately contracted armed security services in Brazil. There are no specific regulations for the embarkation of armed security personnel on convoys navigating the Amazon waterways. The maritime authority allows carriers to engage, under their entire responsibility, accredited companies offering armed security to safeguard the crews and assets on board.

Last year, the Instituto Combustível Legal – ICL (Legal Fuel Institute), an initiative supported by the fuel distribution and petrochemical sectors, published “Manual de Boas Práticas para Proteção de Comboios Fluviais que Transportam Combustíveis” (Best Practices Manual for the Protection of River Convoys Transporting Fuel), in Portuguese only. The Manual provides helpful guidance for river carriers who hire armed security in fuel logistics, noting it does not replace or override regulatory provisions or guidelines issued by competent authorities.

Brazil shares some 8,000 kilometres of poorly guarded borders. In the Amazon, it borders seven South American countries, three of which, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, are the world’s top producers and suppliers of cocaine. It is the largest consuming nation after the United States and a key player in maritime cocaine trafficking. With its extensive inland waterways and coastline, the country became a significant hub for transhipping and launching drug shipments to overseas ports.

Containerised drug shipments depart from Manaus and Vila do Conde (Barcarena) terminals, typically through the “rip-on/rip-off” method. Last year, at the port of Vila do Conde, near Belém, the customs seized nearly three tonnes of cocaine in a container packed with bagged soya bean meal bound for the Portuguese port of Sines, the record-breaking drug bust in a Brazilian port to date. Smuggling drugs on barges and small craft for regional distribution – or transhipment to ocean vessels – is also common.

In an uptrend development that emerged and evolved during the pandemic, cocaine shipments are also concealed in cargo compartments of oceangoing ships, on deck and, more frequently, inside sea chests or attached to the hull, mainly bulk carriers. Incidents of contamination of bulkers were reported in the Amazonian ports of Manaus, Santarém, Santana (Macapá) and Barcarena.

In its World Drug Report 2023, released last month, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) warned that parts of the Amazon Basin are at the intersection of multiple forms of organised crime that accelerate deforestation and other environmental damages and threaten the security, health and well-being of the socially vulnerable and impoverished riverside communities. The Amazon River and its many tributaries are traditional vectors of drug trafficking and convergent crimes.

Drug-related offences in the Amazon include armed robbery, smuggling of wildlife and weapons, illegal mining and logging, land-grabbing, and corruption, as well as all types of crimes against life, such as assault, sexual violation, exploitation of vulnerable workers and minors, kidnapping and murder.

All foreign vessels arriving from abroad to load or unload cargo in Amazonian ports are cleared at the Fazendinha Pilot Station in Macapá, the capital of Amapá, at the mouth of the Amazon River, where mandatory river pilotage begins. Ships must await clearance and take a pilot there before heading upstream. Two pilots are needed for river crossings of more than six hours, which is the case for almost all river ports. A Panamax bulker takes about three days to navigate from Fazendinha P/S to Itacoatiara upriver in the Amazon.

Ships arriving from the Atlantic Ocean, mainly bulk carriers, would typically drop anchor off Macapá to await sanitary inspection to go upriver or wait their turn to berth at the nearby port of Santana, clean cargo holds to load grain, change crew, or disembark seafarers for medical treatment.

Indeed, all six incidents of armed robberies reported since last year in Brazil took place in Macapá and involved anchored bulk carriers.

Reports from the Piracy Reporting Centre of the ICC International Maritime Bureau (IMB PRC) and the IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) show a global decline in piracy and armed robbery incidents in 2022. On the other hand, certain regions in South America, such as the anchorage areas of Callao, Peru, and Macapá in the Amazon, have seen an increase in armed and violent assaults against ships in the same period.

| Date/Time | Type/Flag/GRT | Summary |

| 07.01.2022 06:30 UTC | Bulk carrier Hong Kong 41,718 | The duty crew noticed three robbers armed with guns and knives and informed the officer on duty. The alarm was raised, and the crew mustered. The raiders pointed their weapons at the assembled seafarers as they lowered the ship’s stores onto a waiting boat. |

| 23.01.2022 04:20 UTC | Bulk carrier Singapore 40,341 | Four robbers armed with guns and knives took the OS hostage, threatened, and physically restrained him while they stole the ship’s provisions, having freed the seafarer before fleeing. This ship was attacked again two days later. |

| 25.01.2022 22:40 UTC | Bulk carrier Singapore 40,341 | The Chief Officer noticed two small boats close to the ship and notified the duty AB. While checking the forecast deck, the seafarer noticed two intruders trying to board via the anchor chain. The unauthorised persons escaped without stealing anything. The same ship was also the victim of an attack at this location two nights earlier. |

| 26.04.2022 07:00 UTC | Bulk carrier Marshall Islands 29,407 | During routine rounds, the deck crew spotted three assailants. Given the crew’s alertness and the alarm sounded, the intruders escaped empty-handed. |

| 30.08.2022 04:00 UTC | Bulk carrier Marshall Islands 43,013 | Twenty robbers wearing black face masks armed with guns and long knives beat and tied up six local security guards and duty crew. The master raised the alarm and called port control via VHF. The invaders aborted the attempt to enter the accommodation and ran away with stores stolen. |

| 28.02.2023 02:45UTC | Bulk Carrier Cyprus 34,206 | Five robbers armed with long knives boarded the anchored ship. The duty crewmembers noticed the intruders near the forecastle and informed the duty officer. The alarm was raised, and the ship’s horn sounded. The crew mustered, and the port control was notified. Hearing the alarm and noticing the crew’s alertness, the criminals escaped taking the stolen ship’s stores. |

While there is no record of piracy (as defined by UNCLOS) in Brazilian waters from 2022 to date, incidents of actual or attempted armed robberies are rife in the Amazon region, with almost daily attacks on convoys and small ships.

At the same time, even though the number of attacks against foreign oceangoing cargo ships has decreased from the previous year, they have become more violent. There is likely an underreporting of cases as shipowners and operators fear that local investigations could disrupt the vessel’s schedule and cause even more significant losses for which they are not insurance-backed, such as delays and loss of hire, with little hope that the perpetrators will eventually be arrested and the stolen items returned to the ship at some point.

From January 2022 to February 2023, six instances of armed robbery against commercial cargo ships occurred. All reported cases happened at Macapá anchorage, and the IMB PRC advises vessels visiting the region to remain alert, as local waters remain risky for this type of crime.

Under the maritime authority’s norms and standards for the Amazon and relevant laws, shipmasters and skippers have overriding authority and responsibility to protect their crew, ship and cargo and to adopt preventive measures to ensure the vessel’s safe operation. Likewise, the crews must cooperate in the ship’s surveillance in their own interest and immediately report any suspicious activity to the officer of the watch.

In the aftermath of an assault or armed robbery and as soon as possible, the master must issue a report detailing the circumstances of the event and the preventive measures adopted, along with a description of the perpetrators, their weapons and means used to board the vessel, inventory of items stolen, and if any crewmember has been subjected to violence or other ill-treatment. The report should be forwarded to the Port Captaincy to investigate the breach of maritime security and the Federal Police for the criminal investigation and shared with the flag authority and relevant international organisations.

Please read our disclaimer.

Related topics:

Rua Barão de Cotegipe, 443 - Sala 610 - 96200-290 - Rio Grande/RS - Brazil

Telephone +55 53 3233 1500

proinde.riogrande@proinde.com.br

Rua Itororó, 3 - 3rd floor

11010-071 - Santos, SP - Brazil

Telephone +55 13 4009 9550

proinde@proinde.com.br

Av. Rio Branco, 45 - sala 2402

20090-003 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Brazil

Telephone +55 21 2253 6145

proinde.rio@proinde.com.br

Rua Professor Elpidio Pimentel, 320 sala 401 - 29065-060 – Vitoria, ES – Brazil

Telephone: +55 27 3337 1178

proinde.vitoria@proinde.com.br

Rua Miguel Calmon, 19 - sala 702 - 40015-010 – Salvador, BA – Brazil

Telephone: +55 71 3242 3384

proinde.salvador@proinde.com.br

Av. Visconde de Jequitinhonha, 209 - sala 402 - 51021-190 - Recife, PE - Brazil

Telephone +55 81 3328 6414

proinde.recife@proinde.com.br

Rua Osvaldo Cruz, 01, Sala 1408

60125-150 – Fortaleza-CE – Brazil

Telephone +55 85 3099 4068

proinde.fortaleza@proinde.com.br

Tv. Joaquim Furtado, Quadra 314, Lote 01, Sala 206 - 68447-000 – Barcarena, PA – Brazil

Telephone +55 91 99393 4252

proinde.belem@proinde.com.br

Av. Dr. Theomario Pinto da Costa, 811 - sala 204 - 69050-055 - Manaus, AM - Brazil

Telephone +55 92 3307-0653

proinde.manaus@proinde.com.br

Rua dos Azulões, Sala 111 - Edifício Office Tower - 65075-060 - São Luis, MA - Brazil

Telephone +55 98 99101-2939

proinde.belem@proinde.com.br