Visa exemptions for certain nationalities rei...

read more

Smuggling illicit drugs inside containers and ship hulls continues at high levels, and crews must stay vigilant and take preventive measures whenever in Brazilian ports and anchorages

Despite not being a producer, Brazil remains a strategic hub for the transhipment and trafficking of illicit drugs domestically and across air and sea borders to consumer or intermediary markets in Europe, Africa, and Asia. Between 2017 and 2022, it trailed only Colombia as the top country of origin for cocaine intercepted by law enforcement authorities worldwide, though only about 5% of the global amount was seized in the country.

Following a trend that emerged halfway through the COVID-19 pandemic and continues in full swing, as explained in this circular and this update, the amount of cocaine seized in ports and anchorages, whether hidden inside shipping containers or within or attached to hulls of ships, indicates that the size and frequency of cocaine shipments leaving Brazil by sea remain on the rise, in line with the continued expansion of drug markets and the increase in worldwide consumption and users, as highlighted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in its World Drug Report 2023 released last month.

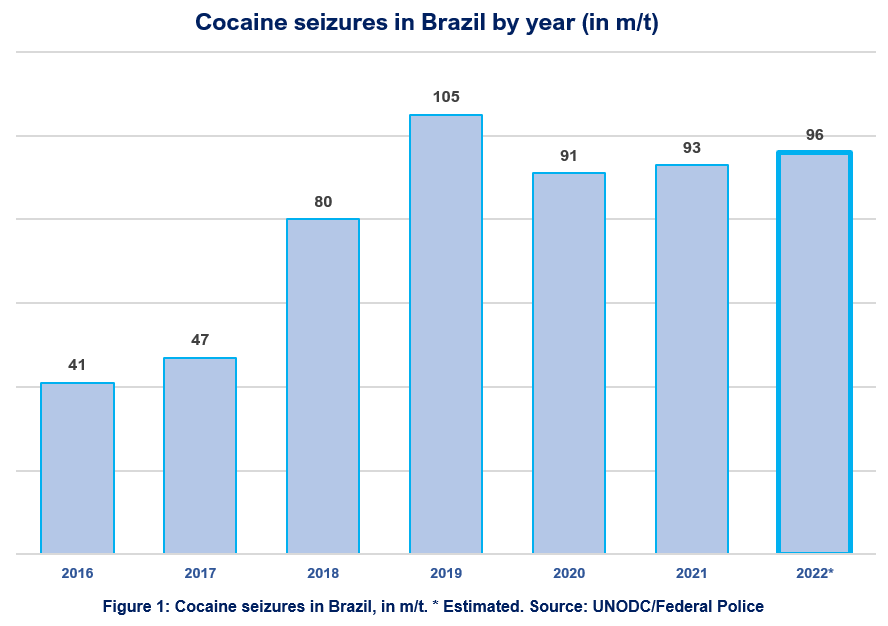

While cocaine volumes impounded within Brazil over the last few years have remained at high but stable levels, a considerably higher proportion of seizures have taken place in ports and terminals across the country, mostly in the larger traditional ports in the south, with Northern Arc ports registering growing volumes in pace with the surge in local port traffic. Figure 1

Higher volumes of maritime cocaine shipments intercepted by police forces in-country and abroad in the last few years are driven by multiple factors, including:

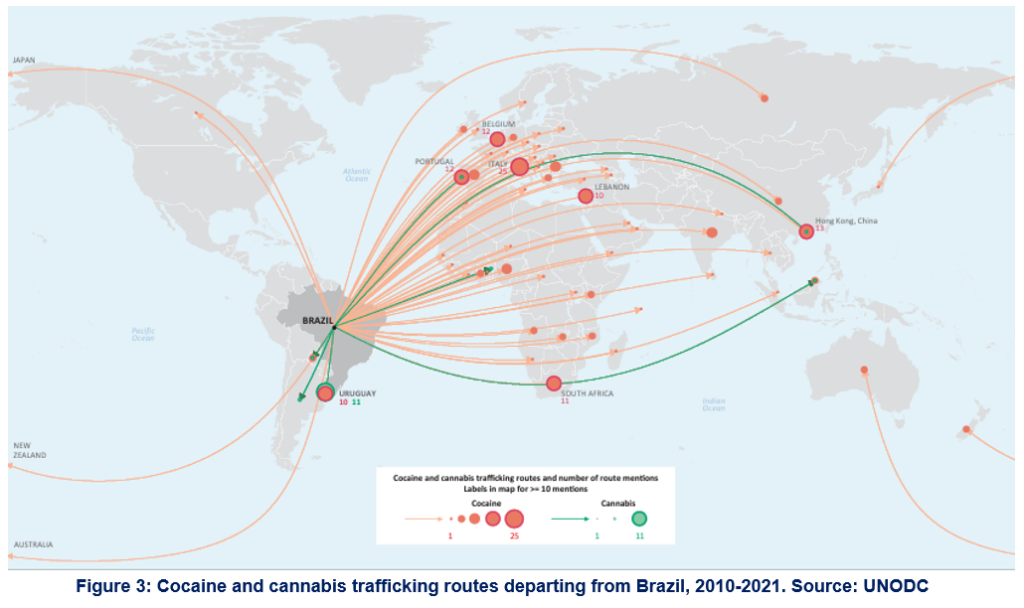

At some point, from 70% to 90% of cocaine exported from South America will cross the ocean before reaching the final buyer. Given Brazil’s long coastline and extensive inland waterways dotted with hundreds of port facilities and terminals, it is not surprising that traffickers widely use Brazilian ports as platforms to launch drug shipments overseas. Figures 2 & 3

Data gathered by the UN drug and crime agency and corroborated by the Federal Police indicates that the stimulant drug is still predominantly trafficked within and between the two major markets in the Americas and Europe, with increasing volumes also being shipped to Africa and Asia. More than half of cocaine shipment interceptions in recent years have occurred in South America, home to the world’s three largest cocaine producers: Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia.

The coronavirus outbreak has triggered changes in maritime cocaine trafficking patterns, such as larger drug consignments, greater use of inland waterways in the Amazon and Southern Cone, and inventive, opportunistic concealment methods.

Containers remain the preferred method of transporting large volumes of cocaine shipments out of Brazil due to their versatility and easy traceability. However, complications brought about at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as global box shortages, supply chain disruptions, heightened security measures at container terminals and strict travel bans, have led resilient traffickers to develop ingenious alternative tactics to adjust the flow and distribution of illicit products and be able to meet the demand that rose throughout the outbreak. Figure 4

While shipping boxes are still widely exploited in the international drug trade, the trend that surfaced at the height of the pandemic – and has been perfected ever since – is to conceal drugs in the submerged areas and compartments of the ship’s hull for later retrieval.

Unlike containerised cocaine, which rarely implicates the crew or carries consequences for the ship, in some jurisdictions across the globe, seafarers have been facing criminal prosecution even when drugs were hidden out of their reach and without evidence of their knowledge or consent.

Organised criminal groups are always one step ahead of public security agencies and constantly change their modalities, routes and networks of partners, financiers, and accomplices to adapt and sustain the flow and profitability of their illicit activities. As the transport of drugs in containers was severely hampered by the pandemic, international traffickers had to look for new ways to continue supplying eager consumer markets.

They went on to systematically smuggle drugs on merchant ships, either by stashing them into cargo holds, void spaces on deck and inside engine rooms and accommodations, or, more recently, by the so-called “parasite modality”, whereby the cocaine is attached to the vessel’s hull below the waterline without the need for assistance or connivance from the crew or payoffs to dock workers or other third parties.

In recent years, most cocaine recovered directly from oceangoing cargo vessels (other than inside containers) was secreted in the hull’s underwater parts, mainly in sea chests, which are only accessible from outside the ship. Local traffickers have been using this secluded compartment extensively to cache drugs. Figure 5

A cavity in the hull below the waterline, the sea chest is fitted with a strainer plate and an inlet reservoir to draw seawater through the vessel’s piping systems for ballast, engine cooling, firefighting, cargo hold washing and other functions. It is usually equipped with a removable grating, offers ideal storage conditions and objects lodged in it can only be detected through an underwater inspection.

Generally, the illicit drug is packaged in watertight bags (with ballast to prevent them from floating), tied together with ropes or straps for better handling and securing underwater. They come in different dimensions, weights and shapes and sometimes include a tracking device. Pictures below

In addition to intelligence work, logistical planning and, above all, opportunity, all it takes is a qualified scuba diver with shipbuilding knowledge to dive from the shore or a small boat, ideally at night, and place the drug packages inside the sea chest or strapped to the underwater hull surface, rudder, bow thruster, etc., and another professional to retrieve the stash at the port of destination. In fact, criminal groups sometimes employ the same dive crew at both ends.

Given the high profitability of maritime drug trafficking, covert divers tend to wear state-of-the-art gear, such as “rebreathers”, breathing apparatuses that eliminate bubbles, thus further hindering detection.

The organisational arrangements of public security forces in Brazil are intricate and decentralised. Different public institutions at state and federal levels act in a fragmented way in repressing (and reporting) drug-related crimes, making it difficult to collect accurate statistical data, even more so when it comes to seaborne cocaine seizures. However, it was possible to gather and analyse quality data from different sources, including the Federal Police (maritime and border police), the Federal Revenue Service (customs), the Centre of Excellence for Illicit Drug Supply Reduction (CoE Brazil), as well as press reports and independent consulting.

From January 2020 to December 2022, law enforcement agencies in Brazil and abroad intercepted nearly seven tonnes of cocaine in the sea chests of about fifty cargo ships of varied types, sizes and flags. During 2020, eight out of nine vessels with contaminated sea chests were containerships. In 2021, five out of thirteen reported incidents involved fruit juice carriers. Last year, of the 26 cargo ships with drugs in that underwater compartment, twenty were bulk carriers. Until April this year, no less than seventeen of the vessels contaminated were bulkers. In one of them, in Italy, no less than a tonne of cocaine was found cached in the sea chest of a bulker carrying wood pulp. Figures 6 & 7

During the research period, some ships were contaminated with cocaine on the sea chest more than once. A couple of them had seizures both at the Brazilian port where the drug was originally hidden and at the port of destination.

As the sharing between Brazilian and foreign criminal police forces evolved over the pandemic, numerous seizures of drug shipments departing from Brazil were intercepted in overseas ports in the last two years. Indeed, in 36 cases surveyed, the drug bust occurred abroad, mostly in Europe, with record-breaking seizures in 2023.

The busy port of Santos on the coast of São Paulo, South America’s largest city, has seen thirteen seizures of cocaine from sea chests of ships, chiefly bulk carriers loading grain and forest products. Most of these contaminations likely occurred at night in the open – and poorly patrolled – anchorage, where the waters are deeper, and visibility is better for diving. Figure 8

None of the seizures in Brazilian resulted in the arrest of the crew or detention of the vessel, with loss confined to the time lost in decontaminating the sea chest, since the Brazilian authorities have been taking the view that, in this modality of trafficking, the drug is placed on ship unwittingly to the crew. Unfortunately, in some cases where the drug was intercepted abroad, crewmembers were prosecuted, and vessels suffered extensive delays.

Underwater inspection services in Brazilian ports and anchorages are allowed as long as they are performed by qualified professional divers accredited by the maritime authority and comply with the “Maritime Authority Standards for Underwater Activities” (NORMAM 15/DPC) issued by the Brazilian Navy’s Directorate of Ports and Coasts (DPC) in 2021 and recently updated.

In some ports, diving companies are licensed and supervised by the port authority. For example, Santos Port Authority (SPA)’s Norm NAP.SUMAS.POR.017 of 28 December 2022 regulates the rendering of underwater services within the organised port of Santos and its anchorage. Among its various provisions, diving companies must inform SPA ten days in advance for underwater repair works to be carried out. In the case of visual inspections and minor repair services, communication can be made within 48 hours before the job start. Vessels undergoing underwaters inspections at Santos roads must be aware of fines for anchoring outside designated areas.

Given the best diving conditions, preventive underwater inspections are usually conducted at the anchorage before the vessel comes alongside. Hull surfaces and compartments are sometimes examined again after leaving the berth and before starting the voyage.

In some ports, arranging underwater inspections can be expensive and time-consuming, demanding planning before the vessel arrives. Furthermore, these preventive inspections, including employing private security guards and sniffer dogs, are not a warranty that the ship is drug-free. There have been at least two cases where owners arranged full anti-drug measures, including dive inspections, yet, drugs were found on board and in sea chests.

There are suggestions that some professional divers legitimately employed by diving companies also provide freelance services to criminal groups for a handsome fee or through coercion or threats against them and their families.

Currently, underwaters surveys are not mandatory anywhere in Brazil. Therefore, we suggest hiring this service – combined or not with other measures, such as sniffer dogs and private security guards – when the master or crew have reason to believe that the vessel’s hull was contaminated while the vessel was waiting to berth or during cargo operations, or in the event any other ship in the vicinity is known to have been contaminated.

Due to the limited visibility and under keel clearance alongside most berths, the best location for the dive inspection is at the anchorage and in daylight, noting that depending on the port involved, there may be some delays in procuring relevant permits from the local authorities. Therefore, anti-drug services must be arranged as early as possible whenever required or recommended.

The UNODC reported that drug smuggling is increasingly compounding and intersecting with other illegal or unregulated activities that harm the environment and threaten the security and livelihood of vulnerable and impoverished populations, such as isolated riverside communities in the Amazon.

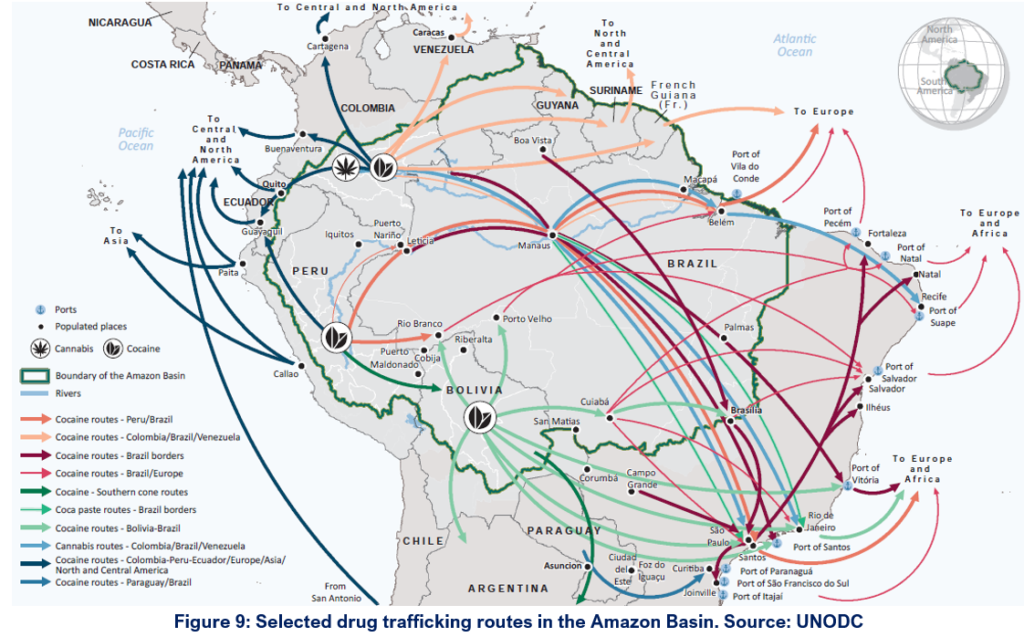

Many of the more than a thousand rivers and tributaries of the Amazon Basin are used as vectors of drug trafficking and converging crimes. The region is chronically menaced by drug, wildlife and weapons smuggling across the vast and poorly policed borders with the Andean countries. In the inland waterways upriver and at the mouth of the Amazon River, armed robberies against barge convoys on the move and anchored ships, illegal gold mining and logging, among other crimes, are also widespread. Figure 9

In addition to environmental damage, criminal activities threaten the well-being of local inhabitants and jeopardise the safety of river navigation, particularly during the dry season.

Although the region is widely used as a gateway for cocaine supplied by the three neighbouring producers, most of the drug smuggled across the extensive Amazonian border (in small boats or private aircraft that land on clandestine airstrips) is transported in various modes to metropolitan regions where half of it is sold to meet domestic demand. The other half is moved to the coast and shipped abroad through seaports, such as Rio Grande, Imbituba, Paranaguá, Rio de Janeiro, Vitória and Santos, the latter standing out as the main point of departure for maritime cocaine trafficking in Brazil.

Despite a relatively low incidence of drug contamination of oceangoing cargo ships calling at the Northern Arc river ports, there are reports of substantial cocaine seizures in sailboats and fishing boats used by local traffickers as drug conveyances. The Federal Police have also seen a sharp increase in drugs concealed in timber consignments for export, mainly to Western Europe.

The largest cocaine shipment ever intercepted in a Brazilian port was in Vila do Conde (Barcarena) near Belém in November 2022, when customs seized nearly three tonnes of cocaine hiding in a container with soya bean meal in bags bound for Sines in Portugal.

Incidents of piracy and armed robbery in Brazil are largely concentrated in the waterways of the Amazon. Nevertheless, even though this risk is small elsewhere in the country, all national ports are subject, to a greater or lesser extent, to maritime drug trafficking, often with dire consequences for the crew and shipowners if the drugs are confiscated at the destination or an intermediary port of call. The driving factors influencing contamination are the opportunity presented and the level of security and surveillance adopted by the port facility and the visiting vessel.

Brazil shares more than 8,000 kilometres of largely unpoliced borders over the Amazon rainforest with the three cocaine-producing Andean countries, as well as 1,365 Km of ground and river crossings with Paraguay in the Southern Cone, a major outpost for transit of cocaine from Bolivia and Peru downstream the Paraná-Paraguay waterway to the River Plate estuary and the Atlantic Ocean where it is transhipped onto oceangoing vessels bound for Europe and Africa.

Its extensive coastline, unguarded inland waterways and borders, and a good air network provide multiple routes for transporting and dispatching cocaine to virtually every continent.

The volume of cocaine busted in Brazilian ports grows year by year. Given that fight against international drug trafficking is fashioned in a poorly structured way, with scarce financial resources available and a general lack of political will, all signs point to the fact that the country is bound to continue to be a key player in the global maritime trafficking of cocaine in the coming years. Therefore, prevention is the only alternative to vessels calling at Brazilian ports and anchorages.

International maritime organisations and P&I clubs have been tackling the problem of seaborne drug trafficking. They regularly publish a wealth of loss prevention material with tips on risk management and preventive measures, international regulatory requirements, and clarification on the scope and conditions of cover afforded for risks arising from the discovery of drugs on board the insured ship.

The most recent authoritative publications on the matter are referenced below, in descending alphabetical order, for further reference and information:

UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): World Drug Report 2023

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS): Drug Trafficking and Drug Abuse on Board Ship 2023-2024 Edition

Centre of Excellence for Illicit Drug Supply Reduction (CoE Brazil): Strategic Study – Covid-19 and Drug Trafficking in Brazil: the Adaptation of Organized Crime and the Actions of Police Forces During the Pandemic

International Maritime Organization (IMO): Revised Guidelines for the Prevention and Suppression of the Smuggling of Drugs…(IMO Resolution MSC.228(82))

NorthStandard: The Evolving Threat of Illicit Drug Trafficking at Sea

West of England: South and Central America – Drug Smuggling

Standard Club: A Wave of Drug Smuggling from Brazil

Steamship Mutual: Brazil: Drug Smuggling

Gard: Ship Operators at Increased Risk of Drug Smuggling

UK P&I: Measures to Prevent the Smuggling of Cocaine

Swedish Club: Drug Smuggling on Bulk Carriers Out of Brazil on the Rise

Japan P&I: Avoiding the Risk of Drug Smuggling

London P&I: Central and South America – increased risk of drug smuggling

Please read our disclaimer.

Related topics:

Rua Barão de Cotegipe, 443 - Sala 610 - 96200-290 - Rio Grande/RS - Brazil

Telephone +55 53 3233 1500

proinde.riogrande@proinde.com.br

Rua Itororó, 3 - 3rd floor

11010-071 - Santos, SP - Brazil

Telephone +55 13 4009 9550

proinde@proinde.com.br

Av. Rio Branco, 45 - sala 2402

20090-003 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Brazil

Telephone +55 21 2253 6145

proinde.rio@proinde.com.br

Rua Professor Elpidio Pimentel, 320 sala 401 - 29065-060 – Vitoria, ES – Brazil

Telephone: +55 27 3337 1178

proinde.vitoria@proinde.com.br

Rua Miguel Calmon, 19 - sala 702 - 40015-010 – Salvador, BA – Brazil

Telephone: +55 71 3242 3384

proinde.salvador@proinde.com.br

Av. Visconde de Jequitinhonha, 209 - sala 402 - 51021-190 - Recife, PE - Brazil

Telephone +55 81 3328 6414

proinde.recife@proinde.com.br

Rua Osvaldo Cruz, 01, Sala 1408

60125-150 – Fortaleza-CE – Brazil

Telephone +55 85 3099 4068

proinde.fortaleza@proinde.com.br

Tv. Joaquim Furtado, Quadra 314, Lote 01, Sala 206 - 68447-000 – Barcarena, PA – Brazil

Telephone +55 91 99393 4252

proinde.belem@proinde.com.br

Av. Dr. Theomario Pinto da Costa, 811 - sala 204 - 69050-055 - Manaus, AM - Brazil

Telephone +55 92 3307-0653

proinde.manaus@proinde.com.br

Rua dos Azulões, Sala 111 - Edifício Office Tower - 65075-060 - São Luis, MA - Brazil

Telephone +55 98 99101-2939

proinde.belem@proinde.com.br